百度医疗广告卷土重来_冷静的技术正在卷土重来,好的设计可以使其坚持下去...

百度医疗广告卷土重来

By Liz Stinson

丽兹·斯汀森(Liz Stinson)

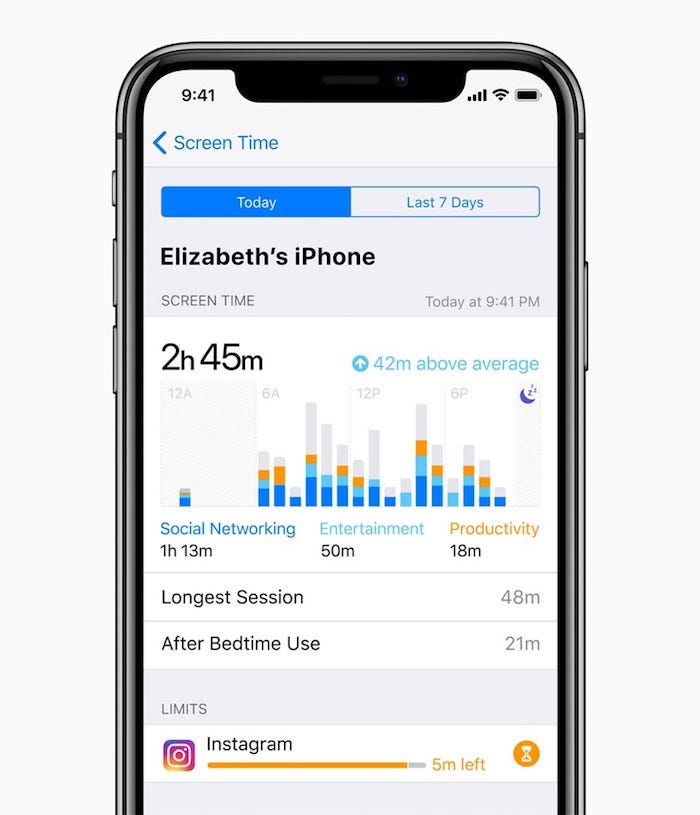

Last week I made progress. I was down 20 minutes. Instead of spending an average of three hours a day looking at my phone, I’d only spent two hours and forty minutes. It was a victory celebrated in slim margins: I’d shaved off time by logging out of Instagram. I checked Twitter only from my laptop. All told, I picked up my phone 52 fewer times than the week before.

大号 AST一周,我取得了进展。 我跌了20分钟。 我每天平均只花两个小时四十分钟,而不是平均每天花三个小时看手机。 这是一次微不足道的庆祝胜利:我通过退出Instagram节省了时间。 我仅通过笔记本电脑检查过Twitter。 总而言之,我接电话的次数比前一周减少了52次。

This information, somewhat ironically, was delivered to me on my phone via Screen Time, a feature Apple launched in fall 2018 to help people understand just how much time they spend looking at the glassy rectangle they purchased from the company. A few months earlier, Google had launched its own version of Screen Time called Digital Wellbeing, which documents phone usage as circular slivers of time, charting everything from how many minutes a person spends on YouTube to the number of notifications they receive in a day.

具有讽刺意味的是,这些信息是通过屏幕时间(Screen Time)通过我的手机发送给我的,屏幕时间是Apple在2018年秋季推出的一项功能,旨在帮助人们了解花了多少时间查看从公司购买的玻璃矩形。 几个月前,谷歌推出了自己的“屏幕时间”版本,称为“数字健康”(Digital Wellbeing),该记录将电话的使用记录为时间的一小段,记录了从一个人在YouTube上花费的时间到一天中收到的通知数量的所有信息。

The apps came on the heels of a rocky couple of years for Silicon Valley’s biggest companies. People (translation: users) had awoken to the startling reality that they couldn’t put their devices down even if they tried. In response there were think pieces and news stories that outlined in detail the intentionally deceptive tactics used by companies like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter to keep people glued to their screens. People like Tristan Harris, an ex-Google design ethicist who founded the Centre for Humane Technology and whose TED talk about the addictive nature of technology has been viewed more than 2.5 million times, have become minor celebrities in certain circles.

对于硅谷最大的公司来说,这些应用程序经历了艰难的几年。 人们(翻译:用户)已经意识到一个令人震惊的现实,那就是即使尝试了,他们也无法放下设备。 作为回应,一些思想文章和新闻 故事详细概述了Facebook,YouTube和Twitter等公司用来使人们黏在屏幕上的故意欺骗性策略 。 特里斯坦·哈里斯(Tristan Harris)是前Google设计伦理学家,他创立了人道技术中心,而他的TED谈论技术的令人上瘾的性质已被浏览了250万次以上,这些人在某些圈子中已成为小明星。

That Silicon Valley’s biggest titans have created apps to limit the usage of their products is a public mea culpa of sorts. After years of building devices, operating systems, and services that were ostensibly created to make people’s lives easier, big tech seemed to finally be admitting, in its own small way, that maybe things had gotten out of hand. Providing people with information (“empowering them”) to learn just how much of their lives they spend on their devices appeared to be the first step in wresting control from phones and tablets and giving it back to the people who used them.

硅谷最大的巨头已经创建了应用程序来限制其产品的使用,这是公众的一种罪魁祸首。 经过多年的建设,表面上创建的设备,操作系统和服务旨在使人们的生活更轻松,大型技术似乎终于以一种自己的方式承认了事情已经失控了。 向人们提供信息(“赋予他们权力”)以了解他们在设备上花费了多少生命,这似乎是从手机和平板电脑夺取控制权并将其交还给使用过的人的第一步。

By the time Apple and Google launched their apps, the great tech backlash had already arrived. In truth, however, the blowback was a longtime coming — more than twenty years, in fact. In the mid 1990s, a group of researchers at Xerox PARC were already thinking about how to safeguard our vulnerable human brains from the tidal wave of information that was heading our way. They called their approach “calm technology,” and its main goal was to figure out how, in an age of technology being everywhere, designers and technologists could build hardware and software that demanded less of our attention, not more.

到苹果和谷歌发布他们的应用程序时,巨大的技术抵制已经到来。 但是,实际上,反冲是一个长期的过程-实际上已经超过20年了。 在1990年代中期,Xerox PARC的一组研究人员已经在考虑如何保护我们脆弱的人脑,使其免受正在前进的信息浪潮的影响。 他们称他们的方法为“平静技术”,其主要目标是弄清楚在无处不在的技术时代,设计师和技术人员可以如何构建硬件和软件,而这些硬件和软件需要我们的关注更少而不是更多。

The future they wanted was not the future we received, and in recent years, the old principles of calm technology have experienced a new resurgence as tech companies try to reverse some of the damage they’ve done by monetizing our attention for years. Apps like Screen Time and Digital Wellbeing are a start — but in this new age of “mindful design,” the question remains: Is calm technology really back, or is it a Silicon Valley-approved version of its former self?

他们想要的未来不是我们获得的未来,近年来,随着技术公司试图通过将我们的注意力货币化多年来扭转所造成的某些损害,平静的技术的旧原则已经重新焕发了活力。 Screen Time和Digital Wellbeing之类的应用程序是一个开始-但在这个“精打细算”的新时代,问题仍然存在:平静的技术真的回来了吗,还是它是硅谷认可的以前的版本?

In 1995, Michael Weiser and John Seely Brown were leading research labs at Xerox PARC, the famed research center in Silicon Valley where technologies like the graphical user interface and ethernet were developed. PARC was a place of open-ended discovery, where technologists were encouraged to explore big questions around how humans and computers interact and what that might mean for the future.

1995年,迈克尔·韦瑟(Michael Weiser)和约翰·西利·布朗(John Seely Brown)是施乐PARC(位于硅谷着名的研究中心)的领先研究实验室,在那里开发了图形用户界面和以太网等技术。 PARC是一个开放式发现的地方,鼓励技术人员探索有关人与计算机如何交互以及对未来可能意味着什么的重大问题。

At the time, Weiser and Brown, along with a researcher at PARC named Rich Gold, were finishing up research around ubiquitous computing (UC), a concept in which computers have embedded themselves so deeply into our lives that we barely notice them. They imagined a future of small networked computers that would serve a single person, not unlike the phones, tablets, and Internet of Things devices that we use today. “The UC era will have lots of computers sharing each of us,” Weiser and Brown wrote in a 1996 paper titled, “The Coming Age of Calm Technology.” “Some of these computers will be the hundreds we may access in the course of a few minutes of internet browsing. Others will be embedded in walls, chairs, clothing, light switches, cars — in everything.”

当时,Weiser和Brown与PARC的研究人员Rich Gold一起完成了关于普适计算(UC)的研究,UC是一种将计算机深深地嵌入到我们生活中的概念,我们几乎没有注意到它们。 他们想象了一个小型的联网计算机的未来,它将服务于一个人,与我们今天使用的电话,平板电脑和物联网设备不同。 Weiser和Brown在1996年题为“冷静技术的来临”的论文中写道:“统一通信时代将有很多计算机共享给我们每个人。” “在几分钟的互联网浏览过程中,其中一些计算机可能是我们可能会使用的数百台计算机。 其他的将嵌入在墙壁,椅子,衣服,电灯开关,汽车中–随处可见。”

In this not-so-distant world, computers would pass unfathomable amounts of information back and forth, creating an interconnected web of data that would allow machines to anticipate our needs and desires. In the utopian version of ubiquitous computing, this anticipatory ability of machines would free humans from the hassle of direct interaction with computers. Our devices would be smart enough to know when to alert us to something we needed or wanted to know, but otherwise they’d fade into the background. In other words, they would be calm. “There was almost a philosophical set of issues coming up,” Brown tells me, in a recent interview, of his time at PARC. “What does it mean to take seriously how you become attuned to something, rather than having to attend to it?”

在这个不那么遥远的世界中,计算机将来回传递大量信息,从而创建一个互连的数据网络,使机器可以预测我们的需求。 在普适计算的乌托邦式版本中,机器的这种预期能力将使人们摆脱与计算机直接交互的麻烦。 我们的设备足够聪明,可以知道何时提醒我们需要或想要知道的事情,但否则它们就会淡入背景。 换句话说,他们会保持冷静。 “在即将发生的一系列哲学问题上,”布朗在最近的一次采访中告诉我他在PARC工作的时间。 “认真对待自己如何适应某件事,而不是必须去关注它意味着什么?”

That big question drove Weiser and Brown’s research. They wanted to understand how to communicate information without hijacking a person’s attention. How could a network of computers augment human intelligence instead of detract from it? Could computers fit into our lives in a seamless and meaningful way?

这个大问题推动了Weiser和Brown的研究。 他们想了解如何在不劫持他人注意力的情况下交流信息。 计算机网络如何增强而不是削弱人类的智能? 计算机能否无缝而有意义地融入我们的生活?

During this period, the researchers on Weiser and Brown’s team built a handful of whimsical experiments that showcased their thinking. In one, an office water fountain changed its flow’s intensity based on the stock prices of PARC. In another, the artist Natalie Jeremijenko hung an eight-foot plastic string from a motor attached to the office’s ceiling. The motor was electrically connected to an ethernet cable, so every time data passed through the cable, it would make the string twitch. A busy network caused the string to whir quickly and loudly; a quiet network would only make the string spin sporadically. “It was part of the physical space,” Brown says of the Dangling String experiment. “Basically, it was measuring the traffic on the ethernet so you never had to pay any attention to it.”

在此期间,Weiser和Brown团队的研究人员进行了一些异想天开的实验,展示了他们的想法。 其中之一是,办公室饮水机根据PARC的股价改变了流量的强度。 在另一幅画中,艺术家娜塔莉·耶雷米延科(Natalie Jeremijenko)用一根8英尺长的塑料绳从安装在办公室天花板上的电机上吊下来。 电机与以太网电缆电气连接,因此,每当数据通过电缆时,都会使字符串抽动。 繁忙的网络使琴弦响亮而响亮。 一个安静的网络只会使字符串偶尔旋转。 布朗谈到“悬空弦”实验时说:“这是物理空间的一部分。” “基本上,它正在测量以太网上的通信量,因此您无需对其进行任何关注。”

The experiments might have seemed trivial in the broader scope of PARC’s research, but these early examples of ambient computing proved an important point about the power of calm technology: Not every piece of information is worthy of immediately capturing your attention, but the information should be there when you need it. More importantly, humans should decide when and how they want to interact with technology — not the other way around.

在PARC的更广泛研究中,这些实验似乎微不足道,但是这些早期的环境计算示例证明了平静技术的重要性:不是每个信息都值得立即引起您的注意,但是这些信息应该在需要的时候在那里。 更重要的是,人类应该决定何时以及如何与技术进行交互,而不是反过来。

During the 1990s, this was a radical idea, or at least an uncommon one. As the designer Amber Case explains in her 2017 book, Calm Technology, computers were still predominantly used for business at the time Weiser and Brown were researching their calm technology principles. “Although it’s common today to talk about bringing ‘humanness’ to digital interaction, at the time, the concept of humanizing technology was right at the cutting edge,” Case writes. “Computers were business, and the challenges of computing were very functional: throughput, processing power, maximizing efficiencies. So, the idea of computing being ‘calm,’ and fitting into everyday life in a way that felt natural, or even enjoyable, was far from most people’s minds.”

在1990年代,这是一个激进的想法,或者至少是一个罕见的想法。 正如设计师Amber Case在其2017年的《 平静技术》一书中所解释的那样,在Weiser和Brown研究其平静技术原理时,计算机仍主要用于商业用途。 凯斯写道:“尽管如今谈论将“人性化”引入数字交互已经很普遍,但在当时,人性化技术的概念才是最前沿的。” “计算机是企业,计算的挑战非常实用:吞吐量,处理能力,效率最大化。 因此,计算是“平静”的想法,并以一种自然的,甚至令人愉悦的方式融入日常生活,这与大多数人的想法相去甚远。”

Weiser and Brown viewed calm technology as a philosophical stance on how computers and humans should interact with each other in the years to come. They didn’t, however, put those ideas into use in any practical sense of the word. After publishing their initial papers on calm technology, the topic quietly faded away. In the years leading up to the smartphone era, the principles behind calm technology were still as relevant as ever, but they had little value in a marketplace that relied on keeping people attached to their devices and constantly upgrading. Advertising, data brokering, and exponential profit forever altered the motivations behind the design of our digital products.

Weiser和Brown将平静的技术视为在未来几年中计算机与人应该如何交互的哲学立场。 但是,他们并没有以任何实际意义使用这些想法。 在发表了有关平稳技术的最初论文之后,这个话题悄然消失了。 在进入智能手机时代之前的几年中,平静技术背后的原理仍然像以往一样重要,但是在依赖于人们与设备保持联系并不断升级的市场中,它们却毫无价值。 广告,数据经纪和指数利润永远改变了我们设计数字产品的动机。

This is something that Brown and his team weren’t actively considering at the time. “We were so romantic in our conception of the good uses of technology and never took very seriously the bad usage of technology,” he says. “Part of the problem, of course, is that today’s digital tools are made complicated because we’re always superimposing ads on everything one way or another, which is a fantastic disruption of things. Some of the things about being able to anticipate needs when deployed on your behalf could be phenomenal, but now we’re using anticipatory techniques to figure out the ideal moment to try to get you hooked on something.”

布朗和他的团队当时并没有积极考虑这一点。 他说:“我们对技术的良好运用的看法如此浪漫,从未认真对待技术的不良利用。” “当然,部分问题是当今的数字工具变得复杂了,因为我们总是将广告以一种或另一种方式叠加在任何事物上,这对事物造成了极大的破坏。 在代表您部署时能够预期需求的某些事情可能是惊人的,但是现在我们正在使用预期技术来确定理想的时机,以使您着迷。”

Within this historical context, it’s easy to see why Silicon Valley is once again attracted to calm technology’s altruistic glow. In the years after Weiser and Brown introduced the idea, consumer technology wandered down the opposite path towards what feels like a wholesale rejection of calm tech’s principles. People were becoming “addicted” to their smartphones and apps, thanks to persuasive design choices deliberately made to keep eyes glued to the screens. Democracy was faltering. Our homes are filled with devices that demand we pay attention. One study found that the average person spends upwards of three hours a day on their phone. Some put the number even higher.

在这种历史背景下,不难理解为什么硅谷再次被吸引来平息技术的无私光芒。 在Weiser和Brown提出这个想法之后的几年中,消费技术朝着相反的方向徘徊,而这种感觉似乎完全拒绝了冷静技术的原理。 得益于精心设计的选择 ,以使人们将眼睛粘在屏幕上,人们对他们的智能手机和应用程序变得“迷上了”。 民主步履蹒跚 。 我们的家庭都充满设备是需要我们注意的。 一项研究发现,普通人每天在手机上花费的时间超过3个小时。 有些人把这个数字甚至更高 。

Calm tech’s core tenet — well designed products respect the user’s time and attention — is a concept tailor-made for a marketing pitch deck of a company that’s looking to rehab its image. “The current interest in calm is because tech is under fire, and deservedly so,” says Mark Rolston, co-founder of Austin digital design studio Argodesign. “They’re trying to save their asses.”

Calm tech的核心宗旨(精心设计的产品尊重用户的时间和注意力)是为希望恢复其形象的公司的市场推广平台量身定制的概念。 奥斯丁数字设计工作室Argodesign的联合创始人马克·罗尔斯顿(Mark Rolston)表示:“目前对平静的关注是因为技术受到抨击,理应如此 。” “他们正试图挽救自己的资产。”

Rolston has spent his career thinking about how to bring Weiser and Brown’s idea of calm technology to life. In 2016, his team showed off a prototype for a project called “Interactive Light,” that reimagined a room as an interactive workspace. A projector cast light onto a desk while a Microsoft Kinect monitored motion. Suddenly you could use gestures to transform the objects in a room into an interface (a salt shaker might become a remote control for your speaker; the countertop could turn into your screen), and the computer would surface whatever tool you needed based on the context of where you were and what you were doing.

Rolston在职业生涯中一直在思考如何将Weiser和Brown的冷静技术理念带入生活。 2016年,他的团队展示了一个名为“ Interactive Light ”的项目的原型,该项目将房间重新构想为交互式工作区。 当Microsoft Kinect监视动作时,投影仪将光线投射到桌上。 突然,您可以使用手势将房间中的对象转换为界面(盐瓶可能成为扬声器的遥控器;工作台可能变成屏幕),并且计算机会根据上下文显示所需的任何工具你在哪里,在做什么。

The concept, while just a prototype, was a playful example of the ubiquitous computing ideas coming out of PARC two decades ago. It made the interface accessible yet more or less invisible. It explored, rather literally, how once the world is overlaid with computational power that can anticipate our needs, we can finally forget the computer is there.

这个概念虽然只是一个原型,但却是二十年前PARC产生的无处不在的计算思想的一个有趣例子。 它使界面可访问,但几乎不可见。 从字面上看,它探索了一旦世界被可以预见我们需求的计算能力所覆盖,我们最终会忘记那里的计算机。

Rolston’s concept is also a bit of an anomaly. Today, so many of the digital products and features we use on a daily basis, from Gmail to notifications to Instagram, are directly at odds with Weiser and Brown’s idea of calm technology. And it’s no real surprise. After all, can technology ever really be calm if it’s supported by a business structure that incentivizes eroding privacy and wringing our attention to the last drop? Probably not, despite the best efforts of companies like Facebook, Apple, and Google to build in guardrails for “responsible” usage.

罗尔斯顿的概念也有点反常。 如今,从Gmail到通知再到Instagram,我们每天使用的许多数字产品和功能与Weiser和Brown的冷静技术理念直接背道而驰。 这并不奇怪。 毕竟,如果技术能够得到鼓励削弱隐私权并使我们将注意力集中在最后一滴的业务结构的支持,技术真的能够变得平静吗? 尽管Facebook,Apple和Google等公司尽了最大努力为“负责任”使用建立防护栏,但可能不会。

For big technology companies to design products that go beyond mere calm-washing will require them to rethink the business motivations that led to these design decisions in the first place. As Arielle Pardes wrote in Wired after Google launched its Digital Wellbeing initiative, “It’s a way to rebrand tech as something that’s good for you — but it only treats the symptoms, not the underlying disease.”

对于大型技术公司而言,设计超出单纯冲洗效果的产品将需要他们重新思考导致这些设计决策的商业动机。 正如Google在启动“数字健康”计划后Arielle Pardes 在《 连线》中所写的那样 ,“这是将技术重塑为对您有益的产品的一种方法-但它只能治疗症状,而不能治疗潜在疾病。”

It’s a cynical view, but it’s fair. The disease itself is complex and hard to cure. We’ve been trained to expect interruption, to crave the opposite of calm. Getting back to a place where technology can co-exist in our lives without co-opting them is going to take more than an app that tells us how far down the rabbit hole we’ve gone. It’s going to take more than temporary life hacks that bring us moments of calm. The hard truth is, technology can only go so far in fixing this problem, which Brown readily admits. “We never viewed technology as solving the problem,” he said in an interview with Medium. “We always viewed technology as a complicating factor.”

这是一种愤世嫉俗的观点,但这是公平的。 这种疾病本身很复杂,很难治愈。 我们已经受过训练,期望被打扰,渴望获得平静的反面。 回到一个技术可以在我们的生活中共存而不被我们选择的地方,它所花费的不仅仅是一个应用程序,它可以告诉我们我们已经走了多远。 它所带来的不仅仅是临时性的 生活骇客 ,这些生活带给我们片刻的平静。 硬道理是,技术只能解决这个问题,布朗很容易承认。 他在接受Medium采访时说:“我们从未将技术视为解决问题的方法。” “我们一直将技术视为复杂因素。”

Still, thoughtful design — calm design — is worth exploring. And people have already started. In her book, Case outlines actionable steps for imbuing digital products with a sense of “calm” (“Consider doing away with an interface or screen entirely, replacing it with physical buttons or lights,” she writes. And “Good design allows someone to get to their goal with the fewest steps.”). But even she acknowledges that rethinking how humans interact requires more than a checklist of design suggestions. Optimistically, the recent resurgence of chatter around calm technology could be seen as the beginning of a tide change, an indication that we’ve reached an inflection point where something has to give. There’s no turning back to a luddite way of life, but Rolston believes that good design will win out. “The presumption is you need this constant flow of interruption, and that’s not a good design,” Rolston said. “I think it’s a mistake that will get undesigned over time. A lot of calm interactions are going to come by us simply deciding we need to know less about what’s going on.”

尽管如此,周到的设计(平静的设计)还是值得探索的。 人们已经开始。 Case在她的书中概述了使数字产品充满“镇静”感的可行步骤(“考虑完全放弃界面或屏幕,取而代之的是物理按钮或照明灯。”她说,“良好的设计使某人能够以最少的步骤即可达到目标。”)。 但是即使她也承认,重新思考人类如何互动不仅需要设计建议清单。 乐观地讲,最近围绕平静技术的of不休可能被视为潮汐变化的开始,这表明我们已经到了必须付出代价的拐点。 没有回头路过的低调生活方式,但罗尔斯顿(Rolston)相信,好的设计会赢得胜利。 Rolston说:“前提是您需要持续不断的中断流程,但这不是一个好的设计。” “我认为这是一个错误,随着时间的流逝,它会变得无计划。 只需确定我们需要对所发生的事情了解得更少,我们就会产生许多平静的互动。”

Liz Stinson is the managing editor of Eye on Design.

Liz Stinson是《 Eye on Design》的执行编辑。

This story is part of an ongoing series about UX design in partnership with Adobe XD, the collaboration platform that helps teams create designs for websites, mobile apps, and more.

这个故事是与 Adobe XD 合作进行的有关UX设计的系列丛书的一部分 , 该协作平台可帮助团队为网站,移动应用程序等创建设计。

翻译自: https://medium.com/aiga-eye-on-design/calm-technology-is-staging-a-comeback-can-good-design-make-it-stick-ec1ec76de7ab

百度医疗广告卷土重来

相关文章:

- 年月日时推算_智能手机联系人追踪的推算日在这里

- matlab中ln、lg函数怎么表示

- C/C++ 求逆序对数

- 负数取反

- 如何使用redis实现动态点赞和反对

- 回归模型中对数变换的含义

- Stata 异方差的处理笔记(搬运)

- 数字图像处理-python基于opencv代码实现 反转变换、对数变换和幂律(伽马)变换

- [数字图像处理]灰度变换——反转,对数变换,伽马变换,灰度拉伸,灰度切割,位图切割

- 数字图像处理学习笔记(八)——图像增强处理方法之点处理

- 灰度变换(反转,对数,伽马)的python实现

- python取相反数_笔试题python基础总结

- 【数字图像处理】灰度变换函数(对数变换、反对数变换、幂次变换)

- 灰度变换,gama变换,对数,反对数变换

- casili计算机按音乐,CASILI计算器怎么按反对数

- python反对数_如何找到一系列n * 0.1(在Python中)最接近反对数(10base)的每个整数

- R语言计算数值的反对数(antilog,antilogarithm)实战

- FreeSwitch(CentOs7.0)+WebRTC(web)+座机呼叫(带SSL注册证书)

- 推荐系统之UserCF2:用户对商品的感兴趣程度

- matplotlib绘制堆叠柱状图、多个柱形图

- 做c4d计算机配置,C4D设计师电脑推荐配置

- RNN模型与NLP应用笔记(3):Simple RNN模型详解及完整代码实现

- hyspider之猫眼价格解密

- 虚幻5降临!再谈谈它的“黑科技”

- 【Keras】IMDB电影情感分析(三种神经网络)

- python爬虫----猫眼电影:最受期待榜

- 很有意思的一个2D转3D电影的解析

- 北美电影票房Top10-2020年2月24日:《刺猬索尼克》惊险卫冕

- yolov5使用2080ti显卡训练是一种什么样的体验我通过vscode搭建linux服务器对python-yolov5-4.0项目进行训练,零基础小白都能看得懂的教程。>>>>>>>>>第二章番外篇

- 盘点技嘉AORUS 2080系列显卡的那些黑科技

百度医疗广告卷土重来_冷静的技术正在卷土重来,好的设计可以使其坚持下去...相关推荐

- 百度医疗广告卷土重来_意见3d电视值得卷土重来的时间

百度医疗广告卷土重来 3D TV's promised a lot to its early adopters, from live sports to a dream cinematic exper ...

- javweb音乐网站_基于JavaWeb技术的音乐网站的设计与实现.doc

基于JavaWeb技术的音乐网站 的设计与实现 本科毕业设计 目录1 1.1 课题研究背景与意义1 1.2 音乐网站的研究现状2 1.3 本论文的结构和主要工作2 第二章 系统环境概述2 2.1 开发 ...

- java 新闻采集系统_基于Java技术的新闻采集器设计与实现

基于 Java 技术的新闻采集器设计与实现 赵敏涯 ; 华英 ; 吴笛 ; 黄鹏 ; 赵明明 [期刊名称] <电脑编程技巧与维护> [年 ( 卷 ), 期] 2019(000)004 [摘 ...

- 饿了么ui组件中分页获取当前选中的页码值_【Web技术】314 前端组件设计原则

点击上方"前端自习课"关注,学习起来~ 译者:@没有好名字了译文:https://github.com/lightningminers/article/issues/36,http ...

- 数字逻辑对偶式_数字电子技术实验——组合逻辑电路的设计

实验目的: (1)掌握组合逻辑电路设计的一般步骤 (2)掌握用TTL基本门电路进行组合电路设计的方法 (3)学会如何查找线路的故障 实验仪器: (1)数字电路试验箱 (2)数字万用表 (3)集成块若干 ...

- 技术12期:如何设计rowkey使hbase更快更好用【大数据-全解析】

HBase是一个分布式的.面向列的开源数据库存储系统,具有高可靠性.高性能和可伸缩性,它可以处理分布在数千台通用服务器上的PB级的海量数据. BigTable的底层是通过GFS来存储数据,而HBase ...

- 10搜索文件内容搜不出_百度搜索广告太多?内容太杂?可能你们缺少这10个神器网站...

百度搜索广告太多,搜索结果内容太杂,有很多虚假无用的信息. 用过百度的应该都有这些体会. 众所周知,百度搜索早已成为互联网基础设施,人人皆知人人都用,给百度贴上"必不可少"的标签都 ...

- 竞价点击软件_百度的关键词竞价广告:百度竞价广告关键词怎么设置?28法则是什么?...

正如百度的竞价推广人员所知,百度搜索竞价推广是一种点击付费的CPC模式,通过竞价购买关键词来争夺有限的广告空间.关键字排位变换分析是日常工作的重点. 许多人刚接触时,总会遇到不能掌握关键字.搜索词等相 ...

- 百度广告产品系统级测试技术演进

背景 根据典型的测试金字塔结构,一个产品的测试可分为三个层级.第一层是单元测试,主要对程序函数进行测试.第二层是集成测试,在百度内部是大家常理解的模块测试.第三层是系统级测试,对产品整体进行的测试.这 ...

最新文章

- RecursionError: maximum recursion depth exceeded

- 柴油发电机并机母线之间母联的设置分析

- 剑指offer03-数组中重复的数字(java)|leetcode刷题

- oracle数据库之数据导入问题

- 路由器上的usb接口有什么用_路由器的USB接口,非常强大的功能,教您轻轻松松玩转,太实用了...

- element-ui表格组件table踩坑总结

- freebsd配置IP

- 两轮差速驱动机器人运动模型及应用分析

- hibernate中的saveOrUpdate()报错

- HDU 4915 Parenthese sequence

- 重SQL开发和重 Java开发比较

- php web开发实用教程答案,PHP Web开发实用教程

- cad图纸比对lisp_cad图纸怎么找出差异?教你怎么对比CAD图纸版本差异

- html表格的形式制作调查问卷,问卷调查表格式,问卷调查怎么制作?

- vue-动手做个选择城市

- STM32控制启动步进电机

- keras中sample_weight的使用

- CF1427E Xum

- android多行文本输入,android EditText多行文本输入的若干问题

- 你们都出去玩吧,我选择宅在家里「憋文章」

热门文章

- mysql5.7.16安装 初始密码获取及密码重置

- SCAU华南农业大学-数电实验-可找零的自动售货机-实验报告

- char const *arg是什么意思

- QGroupBox 显示边框 圆角边框 linux环境

- 读《影响力》喜好有感

- 最小二乘拟合的三种算法推导及Python代码

- 服务器显示错误英文,常见【英文错误提示】解答

- 实现一个模拟工控软件

- Android个人理财通课程设计,android课程设计-小组合作设计开发个人理财通项目.docx...

- The influence of preciseness of price information on the travel option choice文章阅读