Using Markov Chains for Android Malware Detection

If you’re chatting with someone, and they tell you “aslkjeklvm,e,zk3l1” then they’re speaking gibberish. But how can you teach a computer to recognize gibberish, and more importantly, why bother? I’ve looked at a lot of Android malware, and I’ve noticed that many of them have gibberish strings either as literals in the code, as class names, in the signature, and so on. My hypothesis was that if you could quantify gibberishness, it would be a good feature in a machine learning model. I’ve tested this intuition, and in this post I’ll be sharing my results.

What is a Markov chain?

You could just read Wikipedia, but ain’t no one got time for that. Simply put, you show it lots of strings to train it. Once it’s trained, you can give it a string and it’ll tell you how much it looks like the strings it was trained on. This is called getting the probability of a string.

Markov chains are quite simple. The code I used is here: https://gist.github.com/CalebFenton/a129333dabc1cc346b0874407f92b568

It’s loosely based on Rob Neuhaus’s Gibberish Detector.

The Experiment

I’ve been trying to improve the model I use in the Judge Android malware detector. It would have been a lot easier to just create some Markov based features, throw them into the model, and roll with it. But I wanted to be scientific. Everyone thinks science is all fun and rainbows, but thats only in the highlight reel. The real bulk of science, the behind the scenes footage, is tedious and hard. In order to make a data-driven decision about which features worked best and if they helped at all, I took lots of notes of my experiment and preserved all the data. Hopefully, it’s helpful to others.

I started by collecting all of the strings from my data set. For reference, the data set contained ~185,000 samples, about half of which are malicious. Malicious apps are from all over, but many are from VirusTotal with 20+ positives. Benign apps are possibly more diverse and contain strings in several languages.

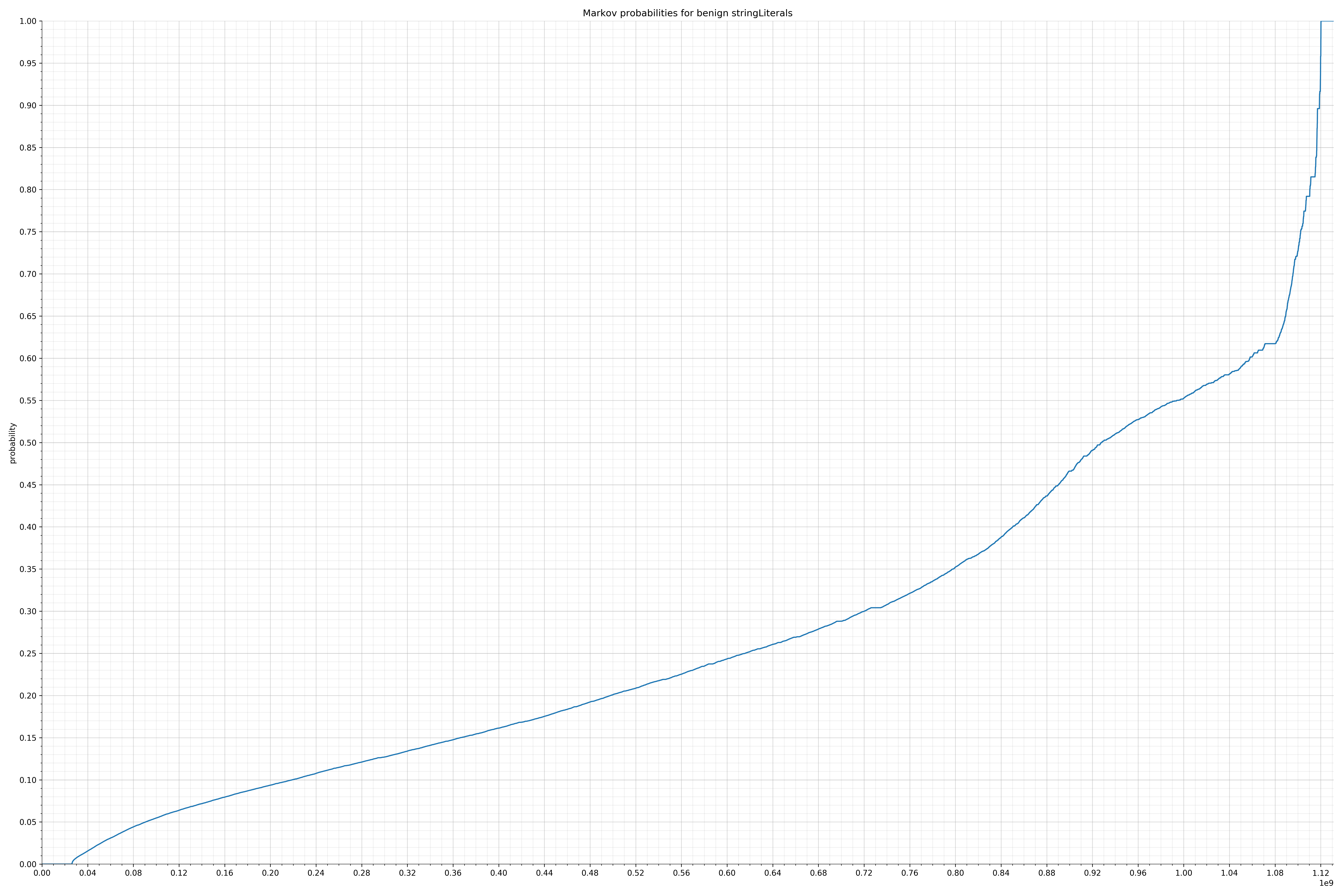

After collecting strings, I trained a Markov model on the strings in the benign apps. For each occurrence of a string, I trained the model on that string. This model would “know” what legitimate, non-malicious strings were probable. Then, I calculated the probability of each benign string and plotted the distribution on a curve.

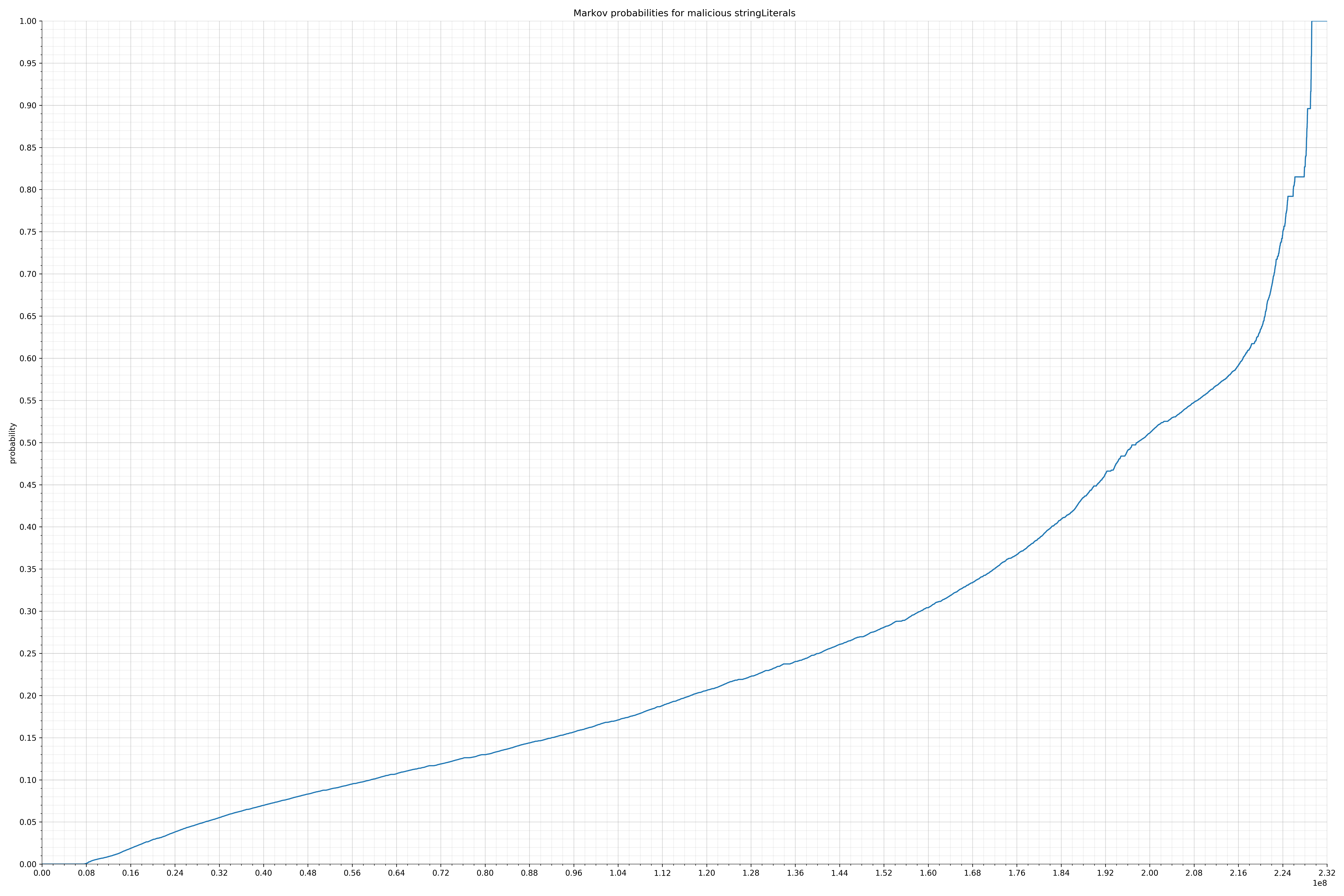

Finally, I used the Markov model trained on the benign strings to calculate probabilities of all the malicious strings and also plotted them. Before I spent time writing any code for features, I wanted to know if there was even a significant difference in probability distribution. If there wasn’t, I would have probably written the code anyway because this is how I spend my weekends, but it turns out there was a significant difference and I felt much more confident the features would be useful.

The Markov chain was configured to use bigrams and strings were tokenized depending on their category. Below are the patterns used:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

|

@Nullable

private static String getTokenSplitPattern(String stringType) {

switch (stringType) {

case "activityNames":

case "receiverNames":

case "serviceNames":

return null;

case "appLabels":

case "appNames":

case "stringLiterals":

return "(?:[\\s+\\p{Punct}]+)";

case "classNames":

case "fieldNames":

case "methodNames":

return null;

case "packageNames":

return "(?:\\.)";

case "packagePaths":

return "(?:/)";

case "issuerCommonNames":

case "issuerCountryNames":

case "issuerLocalities":

case "issuerOrganizationalUnits":

case "issuerOrganizations":

case "issuerStateNames":

case "subjectCommonNames":

case "subjectCountryNames":

case "subjectLocalities":

case "subjectOrganizationalUnits":

case "subjectOrganizations":

case "subjectStateNames":

return "(?:\\s+)";

default:

return null;

}

}

|

String categories and the probability distributions are listed below.

From the Android manifest:

- activityNames - benign / malicious

- appLabels - benign / malicious

- appNames - benign / malicious

- packageNames - benign / malicious

- receiverNames - benign / malicious

- serviceNames - benign / malicious

From the Dalvik executable code:

- classNames - benign / malicious

- fieldNames - benign / malicious

- methodNames - benign / malicious

- packagePaths - benign / malicious

- stringLiterals - benign / malicious

From the signing certificate:

- issuerCommonNames - benign / malicious

- issuerCountryNames - benign / malicious

- issuerLocalities - benign / malicious

- issuerOrganizationalUnits - benign / malicious

- issuerOrganizations - benign / malicious

- issuerStateNames - benign / malicious

- subjectCommonNames - benign / malicious

- subjectCountryNames - benign / malicious

- subjectLocalities - benign / malicious

- subjectOrganizationalUnits - benign / malicious

- subjectOrganizations - benign / malicious

- subjectStateNames - benign / malicious

Comparing the Graphs

Let’s look at a specific example. One of the largest collections of strings were the string literals. These were all the strings that occurred in code. So in the case of String message = "hello,world!";, the string literal is hello,world!.

Below is the probability distribution of benign strings:

benign string literals

benign string literals

Below is the probability distribution of malicious strings:

malicious string literals

malicious string literals

Notice the scale along the x-axis is different between the two graphs, but also note this isn’t as important as the general shape.

In the benign graph, strings are generally of a higher probability, especially at the lower end between 0.01 and 0.05 probability. This would indicate that adding this information to the model would improve model performance.

To add this information as a feature, I collected the probabilities of each string and put them into different bins. For example, for every string with a probability <= 0.01, I incremented the count of strings in the “probability 0.01” bin. The bins were:

|

1

2

3

4

|

double[] bins = new double[]{

0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04, 0.05, 0.06, 0.08, 0.10,

0.20, 0.30, 0.40, 0.50, 1.0

};

|

Notice that bins were more numerous in the lower probabilities to better capture the difference in observed distribution between the two classes (malicious / benign). Similar bin distributions were made for other string categories.

Results and Conclusion

By incorporating Markov features, model performance was fairly improved. Below are the “v1” model scores from a 10-fold cross validation using the top 10,000 features:

|

1

2

3

|

recall: 0.938063119746

precision: 0.979244936027

accuracy: 0.965148875727

|

Below are the “v2” model scores measured in the same way:

|

1

2

3

|

recall: 0.958403081067

precision: 0.984061094076

accuracy: 0.97440419396

|

I regard this as pretty good because every percentage point over 90% is difficult. Also note that these model performance scores are not using the optimal algorithm. I just threw the top 10,000 features into an ExtraTreesClassifier because it’s fast and fairly good. I wasn’t interested in best possible score, only relative improvements. Using a single, well-tuned model, and smarter feature selection, performance reaches 99%.

But 99% is still relatively poor performance for anti-virus, especially for precision, because false positives are so bad. I think the reason for the poor performance is because the malicious test set included adware and injected malware. Adware apps are difficult to distinguish statically and it’s even hard with skilled, manual analysis. Usually, it can only be known by behavioral analysis, i.e. does running this app cause many “annoying” ads to be displayed. By focusing the data set (i.e. cherry picking) more overtly malicious apps, model performance may get a lot better.

So-called injected malware is an otherwise benign app which has had malicious code injected into it. This is uniquely easy for Android malware authors due to the ease of app disassembly and reassembly. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the top features in Judge’s model are from APKiD which can fingerprint the compiler as a proxy for if an app has had code injected into it. This type of malware is also difficult to detect because usually most of the code is legitimate and this means features will reflect a mostly legitimate app.

In any case, further experimentation need to be done to decide which class of malware is most often missed. Once this is known, more features should be added to specifically address that type of malware.

Another remediating factor to consider with using this model is that any real anti-virus solution will be able to generally white list several types of apps to greatly reduce the impact of false positives. For example, an anti-virus company could record which signatures are most common and whitelist all of them. This would preclude the possibility of false positive detections of any popular or system apps.

Future Work

This experiment took two days to run and most of the time was spent extracting features. Also, during that time, my main desktop was booted into Linux and was unavailable for gaming, which was a huge drag. It should be possible to use a smaller data set to reduce iteration time. Maybe I could try 20-50 thousand rather than 180 thousand. samples.

Markov tokenization and n-gram selection can also be adjusted. It’s not clear if bigrams are ideal here. Trigrams may be better, or maybe 1-grams. Maybe it would be better to tokenize string literals only on spaces rather than spacing and punctuation since a lot of obfuscated strings are heavy on punctuation, and it would be good to capture that.

Learning done on the Markov features is probably quite sensitive to how the bins are defined. It may be good to add more bins in the upper ranges, or perhaps even more bins in the lower ranges. Once there are a few data points for performance, it should be possible to algorithmically determine bin sizes and automate some of the guess work. This would make ongoing model updates easier.

It may be useful to filter out commonly occurring classes. Most apps are bloated with common libraries, and by filtering them, the features would more accurately reflect what’s unique to each app. I’ve already created the fingerprinting code, which I’ll write about in a later post. My concern with this is that it’ll require more work to maintain a list of common classes since major libraries are numerous and change frequently.

Reference Data

I’m a big believer in sharing data so people can play with it themselves. Below are links to most of the data for these experiments:

- Benign string counts

- Malicious string counts

- Serialized Markov model

These are compressed JSON files which should be easy to inspect and understand. String counts were recorded rather than strings because the Markov chains were trained by adding each string to the chain for each time it was counted. So if a string was seen 100 times, the Markov chain would have that string added 100 times.

Here’s some example code to deserialize the Markov model. This assumes it’s part of the Jar as a resource.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

|

InputStream is = MarkovLoader.class.getResourceAsStream("/markov_chains.obj");

if (is == null) {

throw new IOException("Markov chains resource not found");

}

ObjectInputStream ois = new ObjectInputStream(is);

Object obj = ois.readObject();

Map<String, MarkovChain> markovChains;

if (obj instanceof HashMap) {

markovChains = (HashMap) obj;

} else {

throw new IOException("Weird markov chain resource");

}

|

Share Comments

原文地址: http://calebfenton.github.io/2017/08/23/using-markov-chains-for-android-malware-detection/

Using Markov Chains for Android Malware Detection相关推荐

- paper—HAWK: Rapid Android Malware Detection Through Heterogeneous Graph Attention Networks

通过异构图形注意网络快速检测Android恶意软件 目录 摘要 一.引言 二.背景和概述 A.动机和问题范围 B.我们的HAWK方法 三.基于HIN的数据建模 A.特征工程 B.构建HIN C.从HI ...

- 【恶意软件检测】【防】DeepRefiner: Multi-layer Android Malware Detection

文中部分内容来自:复旦白泽战队 微信公众号文章 论文链接:点击查看 本文发表在2018 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&a ...

- DeepFlow: Deep Learning-Based Malware Detection by Mining Android Application

题目: DeepFlow: Deep Learning-Based Malware Detection by Mining Android Application for Abnormal Usage ...

- Machine Learning for Malware Detection

Machine Learning for Malware Detection 序 一.恶意软件检测知识基础 数据获取的两个阶段 安卓操作系统架构 安卓应用程序的关键组成部分 特征选择 原始特征数据预处 ...

- 推荐系统论文阅读——Factorizing Personalized Markov Chains for Next-Basket Recommendation

转自博客:https://blog.csdn.net/stalbo/article/details/78555477 论文题目:Factorizing Personalized Markov Chai ...

- 安卓恶意代码数据集(Android Malware and Benign apps)整理

因为最近想做一些简单的实验,而自己之前收集的数据找不着了,所以又看了看别人的推荐,发现ResearchGate上这个讨论里有些回答还是总结得很好的: https://www.researchgate. ...

- 论文-阅读理解-Adversary Resistant Deep Neural Networks with an Application to Malware Detection

整体来说,Adversary Resistant DeepNeural Networks with an Application to Malware Detection 这篇论文是利用了生成对抗网络 ...

- DeepFlow: Deep Learning-Based Malware Detection by Mining Android Application for Abnormal Usage 2

B.恶意和良性的应用程序 我们对3000个良性应用程序和8000个恶意应用程序进行特征提取,其中良性应用程序是从 谷歌播放商店,涵盖了最受欢迎的应用程序在各种类别,后者包括来自恶意软件家族 Andro ...

- android 外文期刊_AndroSimilar: Robust signature for detecting variants of Android malware

[摘要]Android Smartphone popularity has increased malware threats forcing security researchers and Ant ...

最新文章

- UA MATH636 信息论7 高斯信道

- 情人节,你们的CEO都在干嘛?

- 我用 PyTorch 复现了 LeNet-5 神经网络(自定义数据集篇)!

- [iPhone开发]UIWebview 嵌入 UITableview

- 计算机技术qq交流群,专业计算机群QQ

- Java并行编程中的“可调用”与“可运行”任务

- Python3常用数据结构

- java 配置jmstemplate_SpringBoot集成JmsTemplate(队列模式和主题模式)及xml和JavaConfig配置详解...

- 【AI视野·今日CV 计算机视觉论文速览 第233期】Tue, 3 Aug 2021

- 计算机配置cpo,使用域组策略及脚本统一配置防火墙-20210421070355.docx-原创力文档...

- fov视场角计算_图像传感器集成计算功能,赋能机器视觉技术

- ASP.NET Core搭建多层网站架构【11-WebApi统一处理返回值、异常】

- asp向不同的用户发送信息_.Net Core 和 .Net Framework的不同

- python模块:调用系统命令模块subprocess等

- 点击按钮返回上一个页面_零基础跟老陈一起学WordPress 《第四课》用WP半小时建一个商业网站...

- D/E盘根目录出现Msdia80.dll操作;dllregisterserver调用失败错误代码0x80004005 解决

- Android基于opencv4.6.0实现人脸识别功能

- 社区宽带繁忙是什么意思_十年宽带维修工程师给你解读,为什么宽带越用越慢!...

- 计算机培训通讯报道,新员工培训通讯稿3篇

- Linux TC 带宽管理队列规则